Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) is a reference analytical technique for the quantitative determination of metallic elements in a wide variety of samples. Based on the absorption of light by free atoms in their ground state, it allows for the measurement of extremely low concentrations with remarkable precision. Used in fields as diverse as food and beverage , environmental science , pharmaceuticals, and materials , AAS plays a key role in quality control, regulatory compliance, and scientific research. This article explores the fundamental principles of this method, its operation, its main applications, and its analytical advantages.

Table of Contents

Principle of atomic absorption spectrometry

An optical method based on atomic absorption

Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) is an elemental analysis method based on a simple physical phenomenon: the absorption of light radiation by atoms in their ground state. Unlike other spectroscopic techniques based on light emission, AAS measures the amount of light absorbed by a given atom when it is exposed to a monochromatic electromagnetic radiation source emitted at the characteristic wavelength of the element being analyzed.

When a beam of light passes through a cloud of vaporized atoms, some of the radiation is absorbed if its wavelength corresponds to the energy required to excite the electrons of these atoms. This loss of light intensity, measured before (I₀) and after (Iₜ) passage through the atomic medium, is directly related to the concentration of the target element in the sample.

Beer-Lambert's law at the heart of quantification

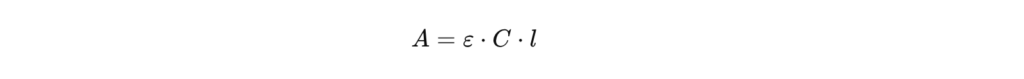

The mathematical relationship between absorbance and concentration is based on Beer-Lambert's law, formulated as follows:

Or :

- A is the absorbance,

- ε is the molar extinction coefficient,

- l is the length of the tank,

- This is the concentration of the solution.

This linear law is applicable within a well-defined concentration range. When the concentration is too high or interferences are present, deviations from linearity may occur, requiring instrumental corrections or sample dilution.

From Kirchhoff to the modern SAA: a continuous technological evolution

The concept of atomic absorption dates back to the fundamental experiments of Gustav Kirchhoff in the 19th century. He demonstrated that the dark lines observed in an absorption spectrum coincided with the bright lines in the emission spectrum of elements heated in a flame. These observations laid the foundation for modern atomic spectroscopy.

The true revolution in atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) occurred in the 1950s thanks to the work of Australian physicist Alan Walsh, who introduced the principle of atomic absorption using light sources specific to each element. This approach allowed for more precise and reproducible analysis, particularly for metallic elements.

Since then, AAS has undergone numerous technological improvements: more stable light sources, background correction systems (such as the Zeeman effect), optimized atomization devices (flame, graphite furnace, hydride generator), automated analysis, and integration of data processing software. These developments have broadened the scope of AAS applications while increasing the sensitivity, reliability, and productivity of this technique.

Today, atomic absorption spectrometry is considered a reference method for the determination of trace metals, thanks to its robustness, specificity and ability to provide reproducible quantitative results on a wide variety of matrices.

Equipment used in atomic absorption spectrometry

Composition of an atomic absorption spectrometer

An atomic absorption spectrometer generally consists of six main elements, arranged in series along the optical path:

- A light source that emits monochromatic radiation at the specific wavelength of the element being studied.

- A modulator , mechanical or electronic, that allows the analysis light to be distinguished from the background noise.

- An atomizer , responsible for transforming the sample into a cloud of free atoms in their ground state.

- A monochromator , which isolates the line of interest by eliminating parasitic wavelengths.

- A detector , usually a photomultiplier, which measures the residual light intensity.

- A data processing system , which converts the light signal into absorbance, then into concentration.

single-beam and double-beam spectrometers . In the single-beam version, the radiation passes successively through the atomizer and then the monochromator before reaching the detector. In the double-beam version, an optical splitter divides the beam into two paths: one passes through the atomizer (analytical beam), the other bypasses it (reference beam). The two signals are compared to correct for source fluctuations and improve measurement stability.

The different light sources used

The quality of the light source determines the selectivity and sensitivity of the measurement. In atomic absorption spectrometry, lamps emitting narrow spectral lines specific to each element are primarily used.

The hollow cathode lamp (HCL) is the most widely used. It contains a cathode made from the metal to be analyzed, a tungsten anode, and an inert gas (argon or neon) under low pressure. An electrical discharge between the electrodes excites the atoms of the cathode, which emit a characteristic line spectrum as they return to their ground state.

The metal vapor lamp is based on the same principle, but contains the element directly in metallic form. It is suitable for easily volatile metals such as sodium or mercury.

Finally, electrodeless discharge lamps (EDLs) are used for volatile elements that are difficult to analyze with hollow cathode lamps (arsenic, antimony, selenium, bismuth). They offer higher intensity and a longer lifespan.

The modulator: signal analysis management

The modulator periodically interrupts the incident light beam to distinguish the useful signal (light absorbed by the analyte) from background noise (stray light or flame emissions). Two types of modulation are commonly used:

- Mechanical modulation by an optical chopper, often a rotating disk that cyclically blocks and releases the beam.

- Electrical modulation using an alternating current power supply to the lamp. In this case, the alternating current allows for the generation of a periodic signal that is easier to isolate and amplify. This method also facilitates the discrimination between photons absorbed by the sample and those emitted by the source.

The monochromator: selection of the line of interest

The role of the monochromator is to filter the radiation transmitted by the atomizer to retain only the wavelength specific to the element being analyzed. It thus eliminates the fill gas lines, secondary lines, as well as any unwanted emissions from the flame or the furnace.

It consists of an entrance slit, a dispersive system (prism or diffraction grating) and an exit slit. The grating decomposes the light beam into a spectrum of wavelengths, and the rotation of the device allows for precise selection of the line of analysis.

The spectral bandwidth (typically between 0.2 and 2 nm) must be chosen to ensure good line separation while maintaining sufficient intensity.

The detector: conversion of the light signal

The most commonly used detector in AAS is the photomultiplier tube . It transforms the light signal transmitted by the monochromator into an electrical signal proportional to the received light intensity. This signal is then amplified, converted, and digitally processed.

Some recent instruments also incorporate photodiodes or diode arrays capable of measuring multiple wavelengths simultaneously. However, these devices are less common in conventional AAS, which remains a single-element method.

Atomization techniques: flame, graphite furnace, hydrides, cold steam

Flame atomization: the most widespread method

The oldest and most commonly used method is flame atomization , also known as flame AAS . It relies on spraying the solution to be analyzed as a very fine aerosol, which is then introduced into a flame from a fuel/oxidizer mixture.

The most commonly used flames are:

- Air/acetylene : temperature around 2300 to 2500 °C

- Nitrous oxide/acetylene : up to 2900 °C, used for refractory elements

There are two types of burners:

- The laminar flame (premixed) burner ensures better flame stability and therefore greater reproducibility of measurements.

- The turbulent flame (diffusion) burner, used in specific contexts where gas safety is a concern.

In this configuration, the nebulizer transforms the liquid solution into an aerosol mist, only a small fraction of which reaches the flame. The droplets are dried and then thermally decomposed, gradually releasing the atoms of the element to be analyzed.

This technique is fast, robust and sufficient for elements present at concentrations above 1 µg/L. However, it is limited by its sensitivity and by the fact that the atomization is continuous, resulting in a significant loss of sample.

Electrothermal atomization: the graphite furnace

For analyses at very low concentrations, electrothermal AAS (or graphite furnace AAS) is preferred. This method relies on a graphite tube into which a small quantity of sample (5 to 100 µL) is deposited using a micro-injector.

The tube is heated by Joule effect according to a three-stage thermal program :

- Drying : solvent removal at low temperature (approximately 100 °C)

- Decomposition or pyrolysis : evaporation of organic compounds and impurities without atomization of the target element

- Atomization : release of atoms at high temperature (up to 3000 °C), in an inert atmosphere (argon)

The oven allows the atomic vapors to be temporarily kept in a confined volume, thus increasing the probability of interaction with the light beam and therefore the sensitivity of the measurement.

This method is well suited to elements present in trace amounts, but it requires rigorous control of temperatures and thermal program, otherwise analytical losses or the formation of interferences may occur.

Hydride generation atomization: a solution for certain volatile elements

Certain elements such as arsenic (As), selenium (Se), antimony (Sb), bismuth (Bi), or lead (Pb) form volatile compounds called hydrides . In these cases, atomization can be improved by a preliminary step of generating volatile hydrides.

The principle is based on a chemical reaction between the analyte (in acidic solution) and a reducing agent , such as sodium borohydride (NaBH₄) . This reaction forms hydride gases, which are then transported by an inert gas to a heated atomization cell , where the hydrides are thermally decomposed to release the atoms.

This technique offers excellent sensitivity and very good selectivity, particularly for elements that readily form hydrides. However, it requires a dedicated hydride generation system, often installed upstream of the spectrometer.

Are you looking for an analysis?

Nebulization and sample preparation

The central role of the nebulizer

The nebulizer is an essential component of the atomization system, particularly in flame mode. Its function is to transform the liquid solution containing the analyte into a very fine aerosol composed of microdroplets. This mist is then delivered to the flame, where the drying, decomposition, and atomization stages can proceed correctly.

Effective nebulization must produce droplets that are as small and homogeneous as possible. Only microdroplets reaching the flame are likely to be properly atomized. Droplets that are too large are either removed by the system walls or carried away by the drain. It is estimated that only about 5 to 10% of the nebulized volume actually reaches the atomization zone, making process optimization essential.

Types of nebulizers

Two main families of nebulizers are used in atomic absorption spectrometry.

The pneumatic nebulizer is the most common type. It works on the principle of drawing the solution in with a jet of gas (often air or argon), creating a vacuum at the outlet of a capillary tube. The liquid is then projected at high speed and atomized into fine droplets. Impact or propeller sorting systems remove the larger particles before they enter the flame.

The ultrasonic nebulizer , much less common in AAS, relies on the vibration of a quartz crystal over which the solution flows. The ultrasonic waves fragment the liquid's surface into an aerosol. This type of nebulizer offers higher efficiency but is more expensive and more fragile.

The choice of nebulizer depends on the viscosity of the solution, the required flow rate, the nature of the matrix and the sensitivity requirements.

Sample preparation: materials and precautions

To ensure the quality of the analysis, the sample must be prepared under controlled conditions. It is generally mineralized using strong acids (nitric, perchloric, sulfuric) to dissolve metallic elements present in ionic or combined form. This step also simplifies the matrix and limits chemical interference.

The resulting solutions are then filtered and transferred into clean, inert, and airtight bottles , usually made of polypropylene or borosilicate glass. These containers must be compatible with the metals being analyzed to prevent contamination or adsorption of the analytes onto the walls.

Here are some best practices to follow:

- Use only containers specifically designed for metal analysis.

- Check the chemical compatibility of the material with acidic solutions.

- Avoid prolonged contact with air to limit oxidation.

- Prepare the stock solutions and standards in the same type of matrix as the sample.

The injection volume is also a critical parameter. In flame mode, the sample is aspirated continuously throughout the analysis. In graphite furnace mode, however, the volume must be precisely measured (often between 10 and 50 µL) and deposited in the center of the tube using a micro-injector. The use of automated injection systems ensures better reproducibility and traceability of the assays.

Particular attention must also be paid to analytical blanks and calibration solutions . The blank allows verification of the absence of contamination of the reagent or containers. Standards, on the other hand, are essential for establishing the calibration curve used in concentration calculations.

Analytical interferences and limitations of the method

Chemical interferences

Chemical interference occurs when components of the matrix form stable or low-volatility compounds with the element being analyzed. This can reduce the efficiency of atomization and lead to an underestimation of the true concentration.

For example, in matrices containing phosphorus, calcium can form calcium phosphate, which is difficult to atomize. Similarly, certain anions such as sulfates or carbonates can precipitate heavy metals as insoluble salts.

To limit these effects, several strategies are possible:

- Add chemical modifiers (complexing agents, masking agents) that prevent the formation of stable compounds.

- Working at higher atomization temperatures (especially in graphite furnaces).

- Optimize the flame composition (rich or lean flame) according to the expected reactions.

Spectral interference

Spectral interference refers to parasitic absorbances generated by species other than the analyte, but which absorb at similar wavelengths. This interference can also result from light scattering by solid particles or from luminescence emitted by the flame or matrix.

They are particularly problematic when the absorption line of the element is close to those of other components present in the sample, or in cases of strong spurious emissions (hot flame, easily excitable elements).

To correct them, several solutions are being implemented:

- Use of a high-resolution monochromator with a narrow bandwidth.

- Implementation of a background correction system , using a deuterium lamp or the Zeeman effect.

- Selection of an alternative wavelength , if one exists for the target element.

Matrix effects

Matrix effects encompass all perturbations related to the physical properties of the sample: viscosity, surface tension, osmotic pressure, and conductivity. These parameters influence nebulization, dispersion within the flame, and the distribution of atoms in the absorption volume.

A sample with a high salt concentration, for example, can lead to rapid crystallization during nebulization, or deposition within the nebulizer, altering signal stability. Biological matrices rich in proteins or lipids, on the other hand, can interact with the graphite tube and disrupt the atomization cycles.

To limit matrix effects, it is recommended to:

- Perform an appropriate dilution of the samples without going below the LOQ.

- Use the method of standard additions , which consists of adding a known amount of analyte to the sample to compensate for the effects of the matrix.

- Employ matrix modifiers , such as aluminum or palladium salts, which stabilize the analyte in the graphite tube.

Technical and analytical limitations

Despite its many advantages, atomic absorption spectrometry has some intrinsic limitations:

- Single-element method : Each analysis requires a specific lamp and calibration specific to the element. It is not possible to analyze several elements simultaneously, except alternately.

- Limited dynamic range : Absorbance follows a linear relationship within a restricted area. Beyond this, the response becomes non-linear, making the results inaccurate.

- Analysis time : Although fast in flame mode, the method becomes slower in graphite furnace or hydride generation, due to heating cycles and successive injections.

- Cost and maintenance : Replacing lamps, maintaining the nebulizer and automatic injection systems can generate significant long-term costs.

Despite these limitations, AAS remains one of the most robust and well-documented techniques for the quantification of trace elements. The combined use of correction devices, appropriate preparation methods, and good laboratory practices minimizes the impact of interferences and fully exploits the analytical potential of this method.

Application areas of atomic absorption spectrometry

Environmental monitoring and regulatory analyses

Atomic absorption spectrometry is widely used in the environmental field , particularly for monitoring the quality of water , soil , sludge , and industrial effluents .

It allows the detection of toxic metals such as lead, cadmium, arsenic, mercury, or hexavalent chromium in very low concentrations, often less than 1 µg/L. These analyses are governed by international standards such as the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) NF EN ISO 5961 standard for the determination of cadmium.

In accredited laboratories, SAA is used for:

- Monitoring of drinking water, surface water and groundwater

- Analysis of waste leachate

- Characterization of polluted soils and sediments

Food safety and nutraceuticals

In the food and nutraceutical , SAA is used to verify the compliance of products with the maximum limits for heavy metal residues set by European regulations.

It is used to measure undesirable elements in:

- Agricultural raw materials (vegetables, cereals, herbs)

- Processed products (juices, food supplements, nutritional powders)

- Food packaging, in connection with migration tests

These analyses make it possible to assess the food safety regulatory compliance (EC Regulation 1881/2006), and to validate nutritional claims regarding mineral content (iron, zinc, magnesium, calcium, etc.).

Cosmetics and personal care products

In the cosmetics , atomic absorption spectrometry is used to detect the presence of metallic contaminants in ingredients or finished products.

The most closely monitored undesirable metals are nickel (Ni) , lead (Pb) , cadmium (Cd) , mercury (Hg) , and arsenic (As) , due to their toxic and allergenic potential. These substances must not be present in finished cosmetics, except in technically unavoidable trace amounts.

The laboratories also analyze:

- Pigments and dyes (iron oxides, titanium dioxide…)

- Sunscreens and moisturizing creams

- Hair or makeup products

The SAA thus makes it possible to guarantee the safety of use and compliance with the cosmetic regulation (EC 1223/2009) .

Animal health and pharmacy

In animal health , SAA is used to assess the mineral content of animal feed , and to detect possible heavy metal contamination in veterinary formulations.

pharmaceutical field , atomic absorption spectrometry is used to control the purity of excipients and active ingredients according to the requirements of the ICH Q3D guideline on elemental impurities. This guideline imposes strict thresholds for elements classified according to their toxicity (groups 1 to 3) and mandates rigorous validation of analytical methods.

Applications include:

- Control of mineral salts (Ca, Fe, Mg, Zn…) in injectable solutions

- The dosage of lead, arsenic, mercury and cadmium in pharmaceutical ingredients

- Verification of inputs from catalytic processes (platinum, palladium)

Control of industrial materials and processes

SAA is also used in the metallurgy , materials chemistry , polymer industries . It enables quality control of raw materials and finished products.

The analyses may concern:

- Metal alloys ( aluminum, steel, brass) to verify their composition

- Surface treatment solutions ( electroplating baths, pickling agents)

- Materials in contact with food , to test for specific migrations

This method is particularly useful in R&D and production laboratories to ensure regulatory compliance (EC Regulation 1935/2004, FDA) , optimize formulations, or analyze manufacturing defects.

Atomic absorption spectrometry analysis services with YesWeLab

A centralized solution for all your elemental analyses

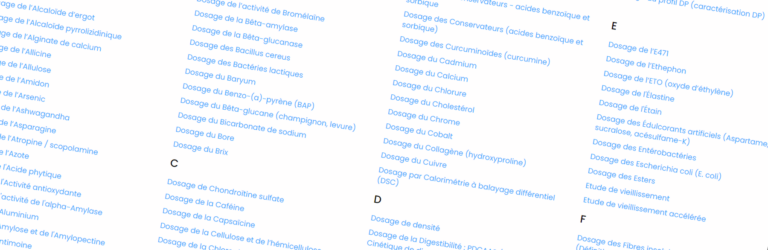

YesWeLab gives you access to a full range of atomic absorption spectrometry analyses , whether for one-off measurements, environmental monitoring campaigns or regulatory compliance validations.

Thanks to an intuitive digital platform , manufacturers can:

- Search and select the analysis best suited to their product or problem from the YesWeLab catalog

- Order your online analysis in just a few clicks

- Track the shipment of samples and the progress of tests

- Download the results directly from a secure area

This simplified operation saves valuable time and ensures complete traceability of operations.

Services that meet the strictest standards

The analyses offered via YesWeLab are performed in ISO 17025 accredited laboratories and, for certain parameters, COFRAC accredited . The methods used comply with current standards.

- NF EN ISO standards for water, soil, sludge, and foodstuffs

- ICH Q3D for elemental impurities in pharmaceutical products

- Regulation (EC) 1881/2006 on metals in food

- Regulation (EC) 1223/2009 on cosmetics

The results are delivered with controlled measurement uncertainty , integrated quality controls, and technical comments where necessary.