Polymers are ubiquitous in our daily lives: from food packaging to medical devices, from paints to technical textiles, they make up a large part of the materials we use. Yet, their molecular nature, manufacturing processes, and physical behavior often remain poorly understood.

Understanding what a polymer is, how it is structured, and how it differs from plastic is essential for industry professionals. In this article, we will introduce the scientific foundations of polymers, laying the chemical groundwork and key concepts of this family of strategic materials, as well as the main methods used to analyze them, such as FTIR spectroscopy .

YesWeLab supports manufacturers in the characterization, quality control and regulatory compliance of their polymer materials through a wide range of laboratory analyses.

Table of Contents

What is a polymer?

Chemical definition of a polymer

A polymer is a macromolecule made up of a chain of small, repeating units, called monomers , linked together by covalent bonds. The regular repetition of these units gives the polymer a high molecular weight and specific physical properties that vary according to its structure, chemical composition, and degree of polymerization.

Monomers can be identical (homogeneous polymers) or different (copolymers), and their assembly can be linear, branched, or cross-linked . This architecture determines the final characteristics of the material, such as its rigidity, flexibility, heat resistance, or solubility.

From a chemical standpoint, two main classes of polymerization can be distinguished:

- Polyaddition of molecules (e.g., polyethylene, polystyrene),

- Polycondensation , which generates a secondary molecule (often water or an alcohol) at each bond formed (e.g., polyesters, polyamides) .

Difference between polymer and plastic

The term “plastic” refers to a ready-to-use material obtained from polymers (base material) and additives (stabilizers, colorants, plasticizers, etc.). Plastic is therefore a processed material , malleable under the action of heat and pressure.

All plastics are made up of polymers, but not all polymers are necessarily used as plastics . For example, synthetic textile fibers (like nylon), adhesives, or even certain technical foams are also applications of polymers, without being classified as “plastics” in the strict sense.

Plastics are characterized by their malleability and their ability to be molded, extruded or injected. Their name comes from the Greek “plastikos” which means “able to be molded”.

Natural, artificial, and synthetic polymers

Polymers are not a modern invention. They have always existed in nature , in the form of biological macromolecules:

- Cellulose (in wood, cotton),

- Proteins (in living tissues),

- Starch , DNA , keratin (hair, nails, wool),

- Natural rubber (from the rubber tree).

We are talking about natural polymers , which humans used long before the industrial era.

Artificial polymers , chemically modified natural polymers . This is the case with rayon (made from cellulose), or collodion (cellulose nitrate), used since the 19th century.

Finally, synthetic polymers are entirely created through chemical synthesis , primarily from petrochemical monomers. These constitute the majority of plastic materials used today, particularly in the food, healthcare, cosmetics, and automotive sectors.

Examples of common synthetic polymers:

- Polyethylene (PE) : bags, films, bottles.

- Polypropylene (PP) : bottle caps, straws, automotive parts.

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) : pipes, flooring.

- Polystyrene (PS) : packaging, insulation.

- Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) : bottles, textile fibers.

These materials are valued for their low production cost, lightness, mechanical resistance and ease of processing, but also pose major environmental challenges, particularly in terms of recyclability and microplastic pollution.

The main families of polymers and their characteristics

Polymers come in a wide variety of materials, classified according to their physicochemical properties, their behavior under heat, and their elasticity. These classifications are essential for determining the appropriate industrial use and the suitable analytical methods. Four main families are distinguished: thermoplastic polymers, thermosetting polymers, elastomers, and polymer matrix composites.

Thermoplastic polymers

Thermoplastic polymers are materials that soften when heated and solidify when cooled , without undergoing irreversible chemical transformation. This behavior is due to their linear or weakly branched , without permanent cross-links between molecular chains.

They can be heated, molded, extruded, and then cooled repeatedly, giving them high recyclability potential . Thermoplastics are widely used in industry due to their ease of processing , light weight , and moderate cost .

Some common examples of thermoplastic polymers:

- Polyethylene (PE) : used for plastic bags, bottles, electrical sheaths.

- Polypropylene (PP) : found in bottle caps, straws, bumpers.

- Polystyrene (PS) : insulating foam, food packaging.

- Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) : bottles, textile fibers.

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) : pipes, joinery, plastic cards.

These materials are often analyzed in the laboratory for their hot melt index (ISO 1133) , their additive composition (GC-MS) or their thermal stability (ATG, DSC), in order to guarantee their good behavior in end use.

Thermosetting polymers

Unlike thermoplastics, thermosetting (or thermoset) polymers undergo irreversible chemical crosslinking during their shaping. Once hardened, they cannot be remolded , as their molecular chains are linked together by covalent bonds forming a rigid three-dimensional network .

These materials are renowned for their thermal resistance , mechanical strength and resistance to chemical agents , but in return are not recyclable by remelting .

Examples of thermosetting polymers:

- Epoxy resins : adhesives, composites, anti-corrosion coatings.

- Unsaturated polyesters : boat hulls, construction materials.

- Phenoplasts (bakelite) : electrical components, pan handles.

- Cross-linked polyurethanes : rigid foams, insulating foams.

These polymers are often subjected to accelerated aging tests crosslinking rate analyses or mechanical characterization (tensile, flexural, hardness tests) in order to assess their performance under extreme conditions.

Elastomers and TPE

Elastomers are flexible polymers with high elasticity : they can elongate under stress and then to their original shape once the stress is released. This behavior is due to their slightly cross-linked and their ability to create reversible physical bonds between chains.

We can distinguish:

- Classic elastomers : natural rubber (NR), silicone (PDMS), EPDM, neoprene.

- Thermoplastic elastomers (TPE) : which combine the properties of an elastomer with the easy implementation of a thermoplastic.

TPEs are often used in the automotive, medical, or sports sectors to manufacture flexible but resistant parts: seals, soles, phone cases, grips, etc.

In the laboratory, these materials are analyzed to:

- their modulus of elasticity ,

- their resistance to deformation or fatigue ,

- their or UV stability (Sun test, ATG tests),

- their Shore A or D hardness , depending on their end use.

Polymer matrix composites

composite materials combine a plastic matrix (thermosetting or thermoplastic) with a reinforcement (glass fibers, carbon fibers, mineral fillers…) to obtain high-performance materials.

The matrix ensures the cohesion of the material and the protection of the reinforcement, while the fibers provide increased mechanical strength, rigidity and sometimes superior thermal resistance.

Examples of composites:

- Carbon-epoxy composites : aeronautics, high-level sport.

- Polyester-fiberglass composites : bodywork, tanks, swimming pools.

- Reinforced thermoplastic composites : skis, technical parts, tools.

Laboratory analysis of these materials often involves:

- the measurement of the charge concentration (TGA, elemental spectroscopy),

- the study of the morphology of the reinforcements (SEM, cross-sections),

- the characterization of porosity ,

- numerical simulation of behavior under constraint (FEM modeling).

These polymer families meet a wide variety of industrial requirements. Their accurate identification, rigorous characterization, and analytical monitoring are essential to ensure the conformity of finished products, whether intended for the food, healthcare, aerospace, or consumer goods sectors.

Are you looking for an analysis?

How are polymers made?

Polymer manufacturing relies on specific chemical reactions that transform simple molecules (monomers) into long macromolecular chains with particular properties. These reactions, collectively known as polymerization , can follow several mechanisms depending on the chemical structure of the monomers and the desired characteristics of the final material. Mastering these processes is essential for shaping the mechanical, thermal, and optical properties of polymers.

Addition polymerization

Addition polymerization ( or chain reaction) involves reacting monomers containing a double bond (usually carbon-carbon bonds) without the formation of byproducts. Once initiated, the reaction progresses rapidly by opening the double bonds to form a polymer chain.

This method is commonly used to synthesize the following polymers:

- Polyethylene (PE) : derived from ethylene

- Polypropylene (PP) : derived from propylene

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) : based on vinyl chloride

- Polystyrene (PS) : made from styrene

- Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) : for organic glasses

The rate of polymerization, the size of the chains, and their distribution (polydispersity) depend on the type of initiator used (radical, anionic, cationic), the operating conditions (temperature, pressure), and the possible presence of inhibitors or solvents.

In the laboratory, these polymers can be characterized by:

- size exclusion chromatography (GPC) to determine their molar mass,

- FTIR spectroscopy to confirm the disappearance of the double bonds,

- DSC calorimetry to evaluate their thermal behavior.

Condensation polymerization

Condensation polymerization relies on a reaction between two complementary monomers, with the elimination of a small molecule (usually water, alcohol, or HCl). This type of polymerization allows the creation of strong covalent bonds between the monomers, resulting in materials that are often more rigid or heat-resistant.

Examples of polymers formed by condensation:

- Polyamides (PA) : reaction between carboxylic acid and amine (e.g., Nylon)

- Polyesters (PET, PBT) : reaction between acid and alcohol

- Polyurethanes (PU) : reaction between isocyanate and polyol

- Polysilicones : polymers containing Si-O bonds

These polymers are widely used in textiles, packaging, construction, and medical devices.

Their analysis may include:

- residual water content tests (Karl Fischer),

- the determination of the crosslinking rate ,

- mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to detect condensation by-products or monomer residues.

Influence of the process on the final properties

The choice of polymerization process directly influences:

- the size of the polymer chains (molar mass),

- the degree of branching or reticulation ,

- the crystalline or amorphous structure ,

- the thermal, mechanical or chemical resistance of the material.

polyethylene (HDPE) obtained by gas-phase polymerization will, for example, be more rigid and crystalline than low-density PE (LDPE) produced by radical polymerization, which will be more flexible and amorphous.

Similarly, the polymerization rate and reaction speed can influence the formation of defects (bubbles, porosity, heterogeneity) observable in the final state, particularly in technical applications.

Quality control and R&D laboratories then use advanced techniques to:

- control the polymerization kinetics (monitoring temperature, pressure, viscosity),

- validate the final structure (spectroscopy, TGA, GPC),

- to ensure reproducibility between industrial batches.

Finally, new techniques of selective copolymerization or polymerization under mild conditions (living polymerization, RAFT, ATRP) open the way to materials with “tailor-made” properties, adapted to cutting-edge fields such as electronics, health or bio-based materials.

Mastering polymerization processes is therefore a strategic step in the development of high-performance, sustainable polymers that are compatible with current regulatory and environmental requirements.

Where are polymers used? Industrial applications

Thanks to their wide range of properties, polymers have become essential materials in many industrial sectors. Lightweight, strong, flexible, or insulating, they often replace metal, glass, or wood in consumer products and technical components. However, their use is governed by strict standards, particularly when these materials come into contact with food, cosmetics, or pharmaceuticals. This section explores the main industries that use polymers, as well as the specific challenges associated with each sector.

Food processing and packaging

In the food industry, polymers are primarily used for manufacturing flexible or rigid packaging . These materials perform multiple functions:

- Protection against oxygen, humidity and UV rays,

- Microbial barrier,

- Ease of transport and storage,

- Marketing communication via labeling or transparency.

Among the most commonly used plastics:

- PET for bottles,

- PE for flexible films,

- EVOH for its barrier properties

- PS for pots and trays.

Regulations mandate specific and comprehensive migration tests to ensure that materials do not release toxic substances into food. These tests are defined in Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 , supplemented by Regulations 10/2011 and 2023/2006. Laboratory analyses allow for the measurement of migration of substances such as:

- plasticizing additives ,

- monomer residues ,

- volatile organic pollutants .

Aging , thermal resistance or labeling compliance tests often complement the evaluation of polymeric packaging .

Cosmetics and health

Polymers are ubiquitous in the cosmetic and medical industries, where they are used in the composition of:

- primary packaging ( bottles, tubes, caps),

- medical devices ( catheters, bags, syringes),

- the formulations themselves (gels, creams, polymer films…).

In this context, polymers must meet strict requirements in terms of:

- biocompatibility,

- absence of toxic releasers,

- resistance to sterilization (by heat, radiation, or ethylene oxide).

Laboratory analysis may include:

- the detection of polymerization residues ,

- the test of extractables and releaseables (particularly for medical devices),

- the analysis of heavy metals , phthalates , or bisphenols .

Compliance with standards such as ISO 10993 (biological evaluation of medical devices) or ISO 11979 (ophthalmology) is essential in this field.

Automotive, rail, aeronautics

In the mobility sector, polymers help reduce vehicle weight , improve impact resistance , and decrease energy consumption . They are found in:

- bumpers (PP, PC/ABS) ,

- interior trims ( PU, PVC, composites),

- sound and thermal insulation materials (PE, EPDM, TPE foams),

- technical engine or chassis parts ( PA66, PBT, PPS, carbon composites).

The polymers used in these sectors must undergo vibration resistance tests , UV radiation tests, extreme temperature tests, and sometimes fire and smoke tests (particularly in the aerospace and rail industries). They must also be digitally modeled to:

- simulate a crash test,

- predict their mechanical behavior,

- validate their integration into a complex production chain.

The tests carried out include:

- dynamic stiffness measurements ,

- acoustic damping tests ,

- nanoindentation or friction wear tests .

Building materials, electronics, 3D printing

Polymers are also used extensively in the construction sector , for:

- insulation materials ( PU, expanded polystyrene, polymer-bonded mineral wool),

- coatings (paints, varnishes, PVC flooring) ,

- windows and joinery (PVC, PMMA profiles).

In electronics , polymers serve as electrical insulators , flexible substrates , and protection against moisture and corrosion. They are found in phones, circuit boards, batteries, and screens.

Finally, with the rise of additive manufacturing , polymers have found a strategic role in 3D printing . The most common materials are:

- PLA (biodegradable polymer) ,

- ABS , PETG , or PA ,

- Photopolymers for resin printing .

Key properties evaluated in the laboratory include:

- resistance (DSC, HDT) ,

- hot fluidity (MFI/MVR ) ,

- quality (porosity, homogeneity, crystallinity) .

Each application area imposes its own regulatory requirements, specific control methods, and performance priorities. This underscores the importance of expert analytical support , such as that offered by YesWeLab, to guarantee the quality and conformity of polymer materials, regardless of their end use.

Why analyze polymers in the laboratory?

Laboratory analysis of polymers is a crucial step in ensuring the quality , safety , regulatory compliance , and functional performance of materials used in industry. Whether during development, production, or defect investigation, analysis allows for precise formulation control , validation of technical specifications , and diagnosis of failures . This section examines the main reasons why manufacturers rely on specialized polymer analysis laboratories.

Objectives of the analysis

a. Identify the material

First and foremost, it is often necessary to confirm the type of polymer used in a part, product, or packaging. This may involve:

- a verification of material conformity with the specifications,

- competitor product analysis ( reverse engineering),

- a comparative study between two formulations.

The analysis makes it possible to determine if the material is PE, PP, PET, PS, PVC , or another polymer, and to detect the presence of additives, mineral fillers or copolymers.

b. Verify the conformity of a formulation

A polymer formulation is composed not only of the base polymer, but also:

- plasticizers (for flexibility) ,

- of antioxidants (stability),

- of colorants , foaming agents , sliding agents , etc.

The laboratory can verify whether the formulation meets the manufacturer's specifications, or if there is a non-conformity that could affect the product's safety or durability .

c. Understanding a failure

In the event of part breakage , deterioration , loss of elasticity , delamination , or adhesion problems , laboratory analysis allows us to:

- observe the defect under a microscope .

- identify impurities or inclusions ,

- detect or chemical degradation

- reconstruct the conditions under which the defect occurred.

This type of analysis is strategic for implementing corrective actions , reducing non-conformities and avoiding quality disputes .

d. Monitor aging or transformation

Polymers are subjected to a variety of conditions: heat, light, humidity, friction, etc. These factors can accelerate their aging . Analysis allows us to:

- measure the stability of the material after use,

- simulate accelerated aging (UV, humidity, thermal cycling),

- observe the effects of recycling or new manufacturing conditions .

It helps to adapt the formulation, to validate a new supplier, or to demonstrate the sustainability of a product in a regulatory or marketing context.

Key moments to analyze

a. During quality control

In the production lines, samples are regularly sent to the laboratory to verify that:

- The batch of raw materials meets the specifications.

- The finished product exhibits the expected mechanical and thermal characteristics.

- The additives are present in the correct proportions.

- process stability is maintained between different batches or lines.

This control is fundamental to avoid customer returns, regulatory non-conformities, or risks related to product safety.

b. At the development or innovation stage

Before launching a new product, a manufacturer must ensure that the polymer used is:

- suitable for its intended use,

- compliant with current standards (food, cosmetics, medical…),

- performing well in the face of mechanical or environmental constraints.

The analysis makes it possible to compare several formulations , to validate an innovation , or to document a regulatory file (particularly in the context of ISO standards or REACH tests).

c. In the event of a dispute or claim

In the event of a customer return or claim , manufacturers call upon laboratories to:

- to examine the part in question,

- establish responsibilities (materials, transformation, use),

- to constitute an independent report that can be used in legal proceedings.

The analyses make it possible to decide between a manufacturing error , a material failure , or misuse .

Polymer analysis is therefore not limited to a single sector or a single phase of the life cycle. It plays a role at every key stage, from design to end-of-life , including production , quality control , recycling , and failure analysis . As such, it constitutes an essential pillar for manufacturers concerned with controlling their materials and ensuring the conformity of their products .

Laboratory polymer analysis techniques

Laboratory analysis of polymers relies on a set of complementary techniques drawn from analytical chemistry, physical chemistry, thermodynamics, and mechanics. These methods allow for the precise identification of a polymer's nature, the characterization of its properties, the detection of potential contaminants, and the simulation of its behavior under operating conditions. Specialized laboratories employ standardized protocols, often accredited to ISO 17025 or COFRAC, guaranteeing the reliability of the results. This section presents the main families of techniques used.

Chemical analyses

a. FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy)

FTIR spectroscopy is a rapid, non-destructive method for obtaining a chemical fingerprint of a polymer. It identifies the functional groups present in the material (CH, C=O, OH, NH bonds, etc.) and thus allows us to:

- determine the polymer family (PE, PP, PET, etc.),

- detect copolymers or mixtures ,

- identify organic pollutants (solvent residues, oils, glues, etc.).

The analysis is often performed in transmission (thin film) or in reflection (ATR).

b. GC-MS and Py-GCMS (gas chromatography – mass spectrometry)

These techniques allow for the analysis of the volatile organic composition of the polymer:

- GC-MS is used to identify additives (antioxidants, plasticizers, stabilizers),

- Pyrolysis-GC-MS (Py-GCMS) allows the analysis of the thermal decompositions of the polymer and the extraction of the signature of the initial monomers.

These methods are widely used for reformulation , detection of prohibited substances , or the study of thermal degradation .

c. LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry)

Adapted for the detection of non-volatile polar compounds , this technique is used for:

- quantify nitrosamines , residual pesticides , or bisphenols ,

- analyze specific migrations in materials in contact with food,

- assess the presence of regulated impurities in cosmetics or medical devices.

d. GPC (size exclusion chromatography)

GPC allows for the measurement of the average molar mass and chain size distribution (polydispersity) of a polymer. It is an essential indicator for:

- to evaluate the mechanical performance of a material,

- compare production batches ,

- detect molecular degradation after use or aging.

Thermal analyses

a. TGA (thermogravimetric analysis)

TGA (Torque-Gestation Analysis) measures the mass loss of a polymer as a function of temperature. It is used for:

- determine the mineral content (glass, fibers, pigments),

- evaluate the thermal stability of the material,

- identify solvent residues or degradation products .

It can be coupled with a gas analyzer (TGA-FTIR or TGA-MS) to identify volatile compounds emitted during decomposition.

b. DSC (differential scanning calorimetry)

DSC measures the thermal transitions of a polymer (melting, crystallization, glass transition). This data allows us to:

- to know the transformation temperature (Tg, Tm),

- to estimate the crystallinity or purity of a polymer,

- monitor the evolution of the material after aging or recycling.

ISO 11357-1 to 7 standards govern DSC analysis of polymers.

Physical and mechanical analyses

a. SEM-EDX (scanning electron microscopy with elemental analysis)

SEM allows observation of the surface and internal structure of polymers at high magnification. Combined with EDX, it also enables elemental analysis . This method is useful for:

- observe cracks, inclusions or porosity ,

- detect metallic pollution ,

- to study interfaces or multiple layers (multilayer films, composites).

b. Nanoindentation, Shore hardness, mechanical tests

The laboratories also perform mechanical tests to evaluate:

- surface hardness ( Shore A/D, nanoindentation),

- tensile strength, bending strength, compression strength ,

- resilience , elastic deformation, rupture .

This data is crucial for engineering polymers, structural parts, or devices subjected to stress.

Aging and durability tests

To simulate the evolution of a polymer in its operating environment, laboratories can perform:

- tests (Sun test) to simulate solar exposure,

- thermal cycles to assess resistance to heat/cold,

- humidity tests , salt spray or solvent ,

- vibration or acoustic testing for applications in the automotive or rail industries.

These tests make it possible to anticipate phenomena such as cracking , discoloration , loss of flexibility or decrease in mechanical performance .

Polymer analysis techniques are therefore numerous and complementary. The choice of methods depends on the nature of the material , the question being asked (identification, conformity, defect, etc.) and the regulatory context .

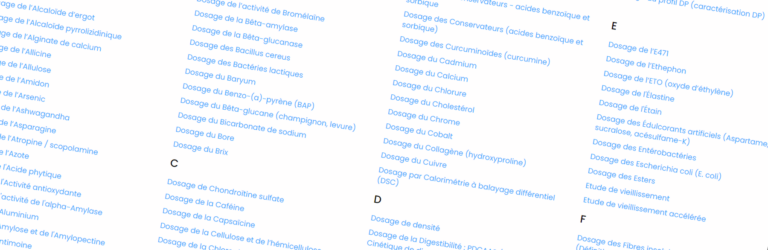

YesWeLab provides manufacturers with a broad network of specialized laboratories to perform these analyses, guaranteeing reliable results that meet industry requirements. See the analysis catalog.